Artist Talk: Season Lao Asian Art Museum in Nice – Special Exhibition Commemorating Catalog Publication

Season Lao × Rui Okabe (Curator of Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art)

Date : 2024.6.8 15:30~17:00

Season Lao Asian Art Museum in Nice – Special Exhibition Commemorating Catalog Publication

City : Fukuoka, Japan

Venue : ギャラリーモリタ (Exhibition : 2024.5.25 – 6.23)

Okabe: Today, in commemoration of the publication of the catalog of Season Lao’s solo exhibition at the Asian Arts Museum in Nice, I would like to ask him about the exhibition and what inspires his works.

Okabe: I would like to start by asking something related to your home; Macau. Martinho Hara was a 16th century catholic priest from Kyushu, Japan. He was one of the four delegates to visit the Pope and Europe as part of the Tenshō embassy. When Chrisitanity was banned in Japan, he moved to Macau where he eventually was buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Lao, You were involved in a project which installed a 14-meter snow sculpture of the ruins of St. Paul’s Cathedral at the Sapporo Snow Festival in 2016. Would you please tell us about your own relationship to Christianity and Macau.

Lao: Macau’s culture is mainly a mixture of Buddhism, Taoism, and Christianity. I was born into a Chinese family during the Portuguese Macau. Personally, I am not a follower of any particular religion. However, Macau has a strong connection to religion. The official Portuguese name for Macau was “Cidade do Nome de Deus de Macau,” which means “City of The Name of God of Macau” and shows the connection to Christianity. The snow sculpture was of the facade of St Paul’s Cathedral. The cathedral was adjacent to St. Paul’s University, the first Western-style university in East Asia and has since become a recognized symbol of Macau.

Okabe: Portuguese missionaries used Macau as a base to spread Christianity throughout Asia. Missionary activities were also carried out in Japan, but the government of the time felt threatened by Christianity and suppressed it. Among the artworks of Japanese Christians is a ‘secret’ statue of Mary called “Mary Kannon” which looks like a Bodhisattva. There was no suppression of Christianity in Macau, but is there a fusion of Christian and Eastern cultures like the statue of “Maria Kannon”?

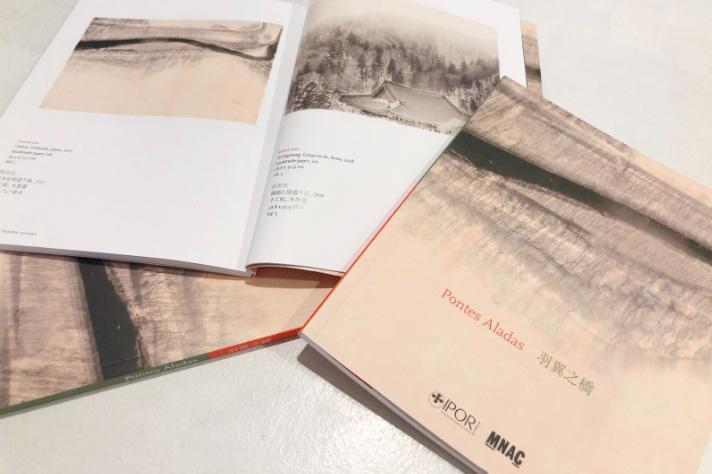

Lao: What you said reminds me of the “Garden of the Cross,” a rock garden built in memory of Otomo Sorin, which I saw at Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto. To your question, Yes. In Macau, there is a sculpture in the ruins of the Jesuit St. Paul’s Cathedral that incorporates some Eastern elements. When I was a child, I was impressed by paintings in the Church of St. Francis Xavier, where Xavier’s relics were enshrined. The paintings blended images of the Virgin Mary, the Bodhisattva of Mercy, and the Taoist goddess Matsu. By the way, the Portuguese National Museum of Contemporary Art curated a Macau-related exhibition in 2019 titled “Pontes Aladas” (Winged Bridges) and included my work “Natural Emptiness.” (自然余白)

Museum of Contemporary Art ポルトガル国立現代美術館企画

Okabe: Around 2007, while you were a student at Macao Polytechnic University, you created video works about the history of Chinese and Portuguese communities in Macau. The films were exhibited at the Macau Cultural Center, Guangzhou Art Institute, and a Museum in Taiwan, among others. How did you come to create “Pateo do Mungo” which marks the start of your artistic career?

Lao: In the 2000s, Macau opened its casino management rights to foreign capital. There was a rush to build resorts including ones affiliated with major Las Vegas brands. Against this backdrop, I was enrolled in evening classes at the only art university in Macau at the time. During the day, I researched the changes in local culture and engaged in activities such as video archiving.

The first of the two videos that resulted from this work was a reflect on the Portuguese community in Macau. In Macau, the people of mixed Chinese and Portuguese heritage are called Macanese. We went to San Francisco and Lisbon to hear the stories of Macanese migrants.

The other video, “Pateo do Mungo (百年菉荳圍)” is about the Chinese community in Macau. In particular, It is about a group of historical buildings, including my birthplace, that date back to the Qing Dynasty. These buildings were originally scheduled to be demolished, but the demolition was canceled due to the response to my work and the publication of a collection of my works. This was a rare occurrence in Macau at that time when land prices were skyrocketing to save something of cultural value.

Okabe: Lao, you lived in Hokkaido for 10 years from 2009. Why did you choose Hokkaido?

Lao: My stay in Hokkaido was by chance. At the time, I was doing my internship period that was part of my university studies. Initially, I had wanted to experience the simplicity of Scandinavian life. I received an offer from a Norwegian company, but I decided against it because there was no foreign precedent at my university and I could not get a visa in time.

I had several other options, including San Francisco, and Berlin, and chose Date City in Hokkaido, Japan, as it had the most rustic feel out of all of them. After my internship was finished, the company then asked me the following year (2010) if I would like to join them in Sapporo.

Okabe: You mentioned in your book that you were exposed to ‘pure experience’ in Hokkaido and created works related to “emptiness” in natural phenomena. Could you tell us more about your work during time?

Lao: The instigator was experiencing a strong snowstorm for the first time in my adult life while I was in Date City. Being enveloped completely in white snow, I experienced consciousness that was undivided between subject and object. This experience faded away as I returned to my daily life, but stayed with me. The following year, around the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake, I was reminded of it as well as its impermanence. This led me to start creating works on “Natural Emptiness” independent of my job.

Okabe: Nature in Hokkaido had a great influence on and triggered your creative activities, didn’t it?

Lao: Yes, nature in Hokkaido has a richness. I think that the fact that nature has not been objectified by humans makes it possible for my sensitivities to work. It is truly a blessing.

Okabe: As a contemporary artist, you express yourself through various media. Among these are the works related to “Natural Emptiness” which use photography as a means of expression. In 2014, you were selected by the Macao Museum of Art to participate in macau pavilion at the 14th China Pingyao International Photography Festival, and in 2015, you participated in a project curated by the city of Como, Italy, titled “L’uomo e il paesaggio,” a photography-related project. What are your thoughts on photography as a medium?

Lao: I think that photography can serve as a substitute for the human eye. In other words, it is a medium that is connected to the phenomenal world. It has a kind of ambiguity that is similar to the human body in that, despite being material, it is capable of reflecting non-material aspects of reality as well such as perception.

The relationship between the objectifying field of photography and the fine arts is complex. For example, 19th century painters used photography as a preparatory sketch and photography was used to imitate oil painting in the age of Pictorialism during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Now, photography is often used in today’s consumer society and has a more social and convenient nature; which means it is a medium that is heavily biased in that direction. The moment one hears the word “photograph,” some people fall into a self-defeating act of trying to completely describe it. This failure of the mind to understand things fully was recognized even a few hundred years before photography, during the European Enlightenment, which resulted in Idealism.

Roberto Borghi, Andrea Giordano, Michele Pierpaoli Carlo Pozzoni Fotoeditore | Italian | ISBN : 9788890963353

Okabe: Lao, having traveled all over the world and in Japan, why did you decide to base yourself in Kyoto in 2020?

Lao: Since 2016, I have had more opportunities to go overseas for exhibitions. In terms of logistics, I thought it would be better to have a base on the main island of Japan; Honshu. I was very familiar with the Kansai area as I receive requests to serve as a judge in Osaka every year. There is also a planning gallery in Kyoto which represents my works. I am also a member of a planning gallery in Kyoto. During the pandemic I moved my base from the center of Kyoto city to a rural village outside of the city.

Okabe: Your work ‘Lotuses’ was released in 2019. It was exhibited at the Wilson Museum in Vermont, U.S.A., among others. From the perspective of your work and Asian art, What are your thoughts on the concepts of ‘between’ (間) and ‘emptiness’ (余白)?

Lao: ‘Between’ and ‘emptiness’ are at the center of all Eastern thought, as is the concept of ‘emptiness’ (無). It is also visible in the Kitayama and Higashiyama schools of Japanese culture. Although the context is different, ‘emptiness’ is often found in American minimal art, which seeks to express entirety. The original of “Lotuses” is a frozen lotus pond I encountered in the Tohoku region of Japan. The ‘emptiness’ of the lotus serves to remind us of the cycle of life. The piece was once exhibited at the same time as a work by the American minimal artist Sol LeWitt.

The exhibition space of the collections of “Lotuses” varies. In Niseko, it is installed in a tea room inside a resort hotel. In Mino, it is installed in the middle of a historical tea room that represents the yin-yang relationship. In Asakura, it is installed in a wooden storehouse, called a hojo itakura (方丈板倉), which was made of wood damaged by torrential rains in northern Kyushu and evokes a sense of impermanence.

Nipponia Mino merch ant town historic tea house collection | Nipponia 美濃商家町茶室 コレクション

Okabe: The Ritz-Carlton, Fukuoka, which opened in 2023, also has a permanent exhibit of your work related to ‘Natural Emptiness’ related works. I understand that this work is related to Kyushu, but how so?

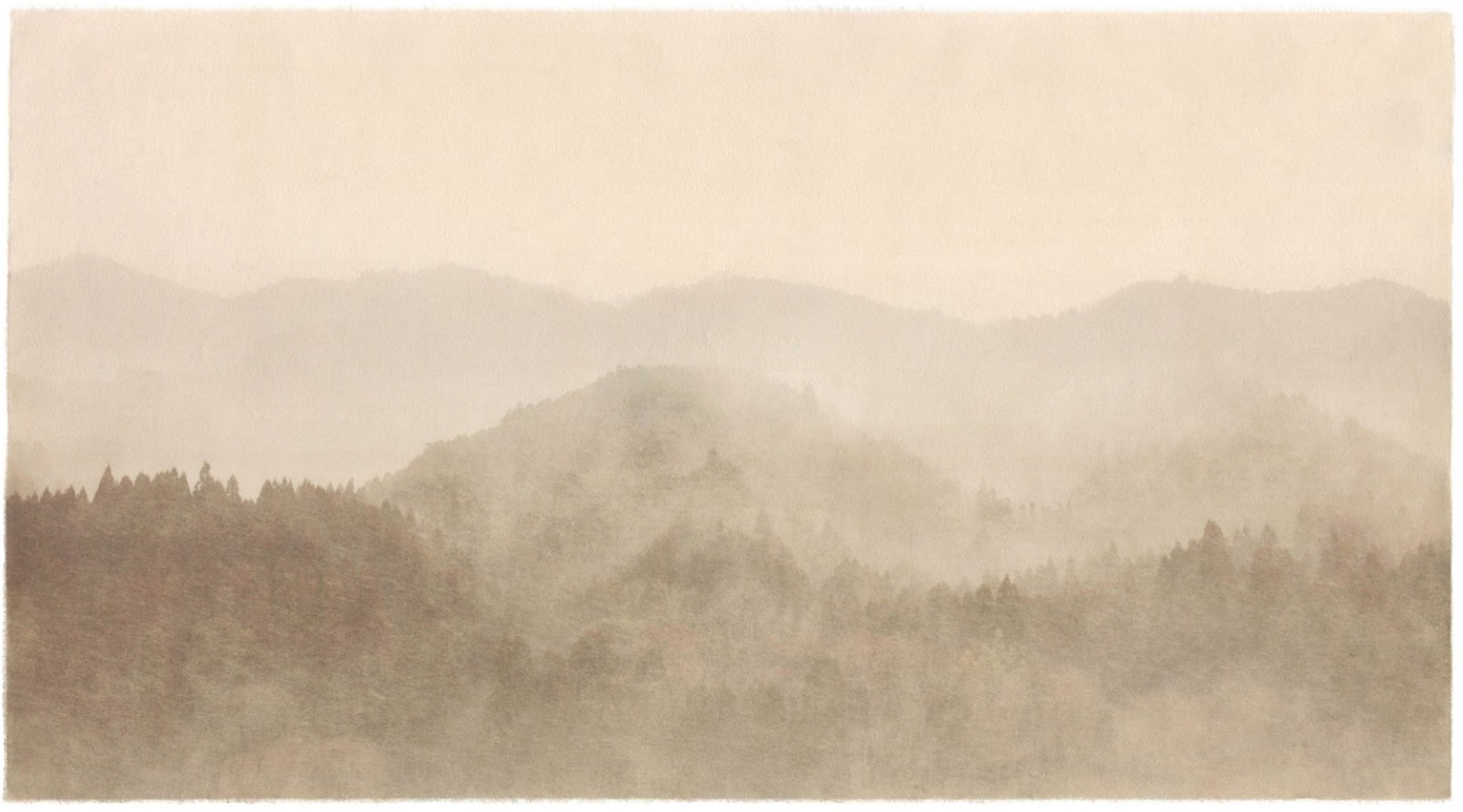

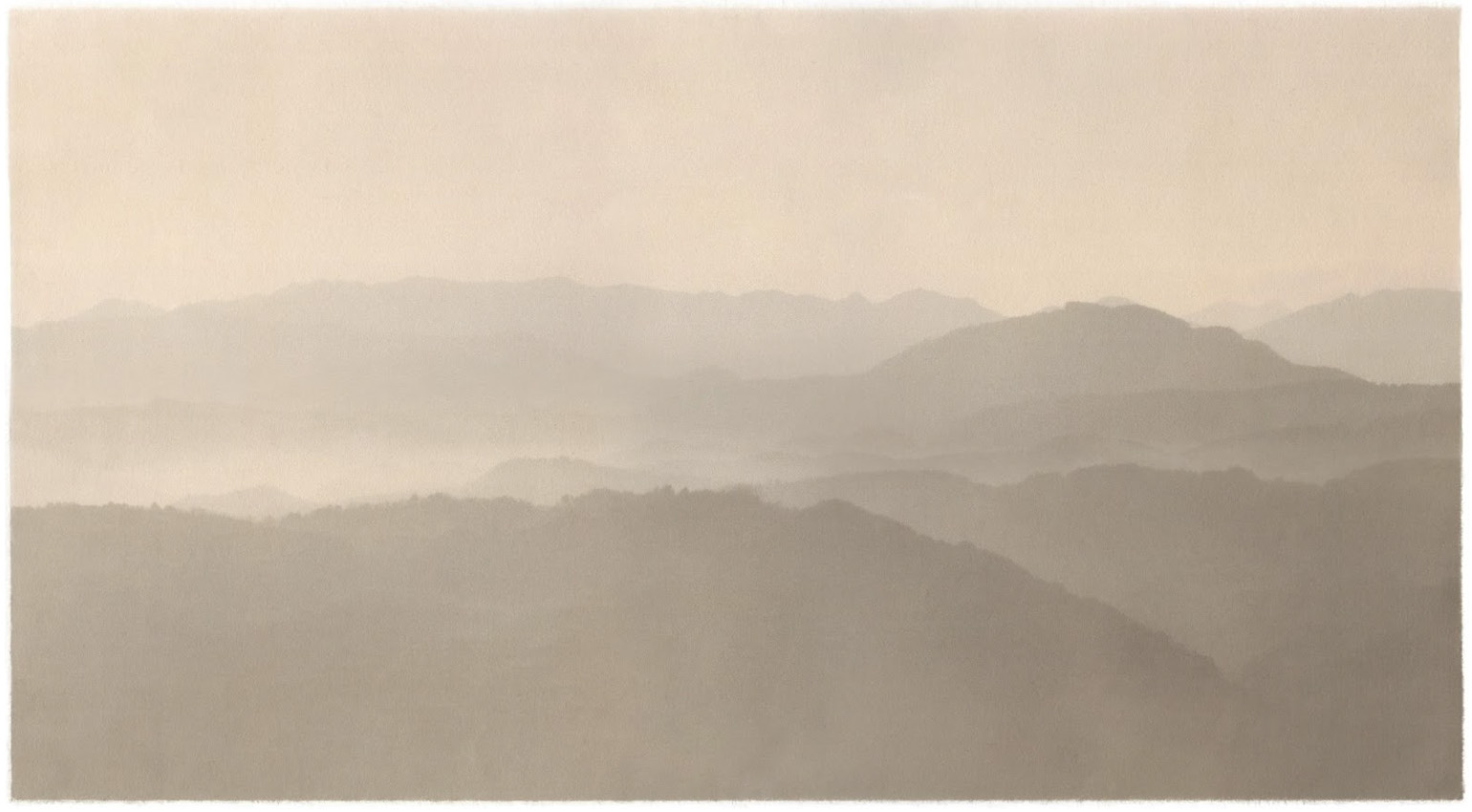

Lao: In the hotel lobby on the 18th floor, there are works covering various areas of Kyushu. There are images of snow from Tenzan, Saga, mist from Asakura, Fukuoka, and fog from Takachiho, Miyazaki. This variety of scenes is the reason I still travel around Kyushu. I was impressed by the scene of mist from Mt.Takachiho which is a sacred mountain and the towering cedar trees from Mt. Hiko.

The Ritz-Carlton collection

The Ritz-Carlton collection

Okabe: I would like to ask you about the relationship between your work on ‘natural emptiness’ (自然余白) and ‘dependant co-arising’ (縁起).

Lao: The source of my work is encountering natural phenomena in a relationship which I call ‘engi’ (縁起) or ‘dependent co-arising.’ The moment one is surrounded by mist, the opposing concepts of ‘here’ and ‘there’ disappear. The place where one is becomes emptiness, or one becomes part of the scene itself. In this moment the interdependence of emptiness and reality is realized via natural phenomena like fog and snow, and one reflects on the ‘infinite’ spanning from one’s heart into the distance.

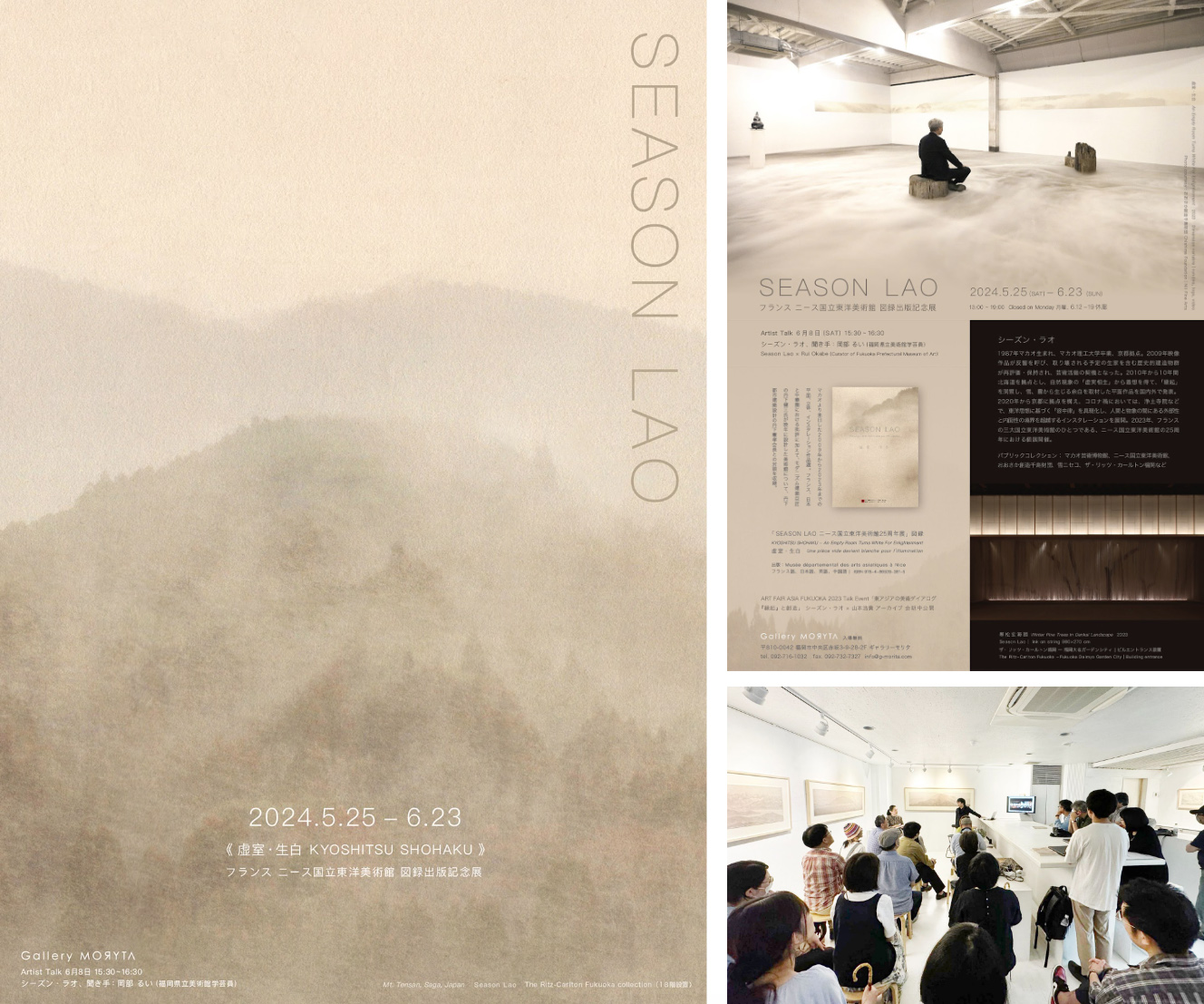

Okabe: Was the installation performance “KYOSHITSU SHOHAKU – An Empty Room Turns White for Enlightenment.” which appeared in your solo exhibition at the Asian Art Museum in Nice, France, in 2023, also inspired by ‘natural emptiness’?

Lao: During the COVID-19 pandemic, I started to conduct private experiments at a Cultural Heritage Temple in Kyoto. The gardens at the temple reflect the buddhist idea of the ‘pure land’ and I used these gardens as the location for an installation called “Visible and Invisible” (可視・不可視). The installation was an attempt to explore a phase between human beings and natural phenomena that cross the boundary between subject/object and interior/exterior. I think it is proper to call such an undivided nature of subject and object “the law of included middle.” Thus, this earlier work served as a kind of prototype for “Kyoshitsu Shohaku – An Empty Room Turns White for Enlightenment.” installation.

Hojo garden, Honenin Temple Kyoto 2021

SEASON LAO | Dimension variable | Gallery Garage KG+ 2022

Okabe: So rather than working with the relationship between subject and object, your approach is to merge the two. Law of Included Middle (容中律) and ‘dependant co-arising’ (縁起) are important keywords in your work. Is it correct to understand the Law of Included Middle as a removal of boundaries, or being both and neither at the same time?

Lao: In Eastern thought there is the concept of ‘Tiān rén héyī (天人合一),’ which is the unification of man with nature. This means that humans and nature are included in one another. At the Asian Art Museum in Nice, the glass-formed space I chose for the installation looks out on a pond. It reminds one of the sensation of looking down at the sand or raked gravel grounds from the raised floor of the academy building in a Pure Land Buddhist style garden, where the raked gravel is made to look like ocean waves. This space, which is a traditional Japanese veranda, called an “engawa,” connects the inside with the outside. In ‘Kyoshitsu Shohaku (虚室・生白)’, stumps from trees that have been cut down by natural forces are placed. These blend into the surrounding landscape. An anonymous figure is seated on the stump, and fog is generated from the space. This work seeks to dissolve the boundary between subject and object, as well as the possibility of the Law of Included Middle (容中律).

Dimension variable | logs of Alpes-Maritimes, video Asian Art Museum in Nice | ニース国立東洋美術館 2023

Okabe: On the criticism of Liao Hsin-Tien (廖 新田) said about your work,

“Season Lao believes that art should not emphasize the superiority of materials and techniques. In other words, crossing the physical boundaries of artworks through the “transmutation of substances” is what the art experience pursues for him.”

Indeed, I feel that when I stand in front of your work, I have a sense of being involved in an auspicious event, like I am reliving it, and I can encounter your worldview.

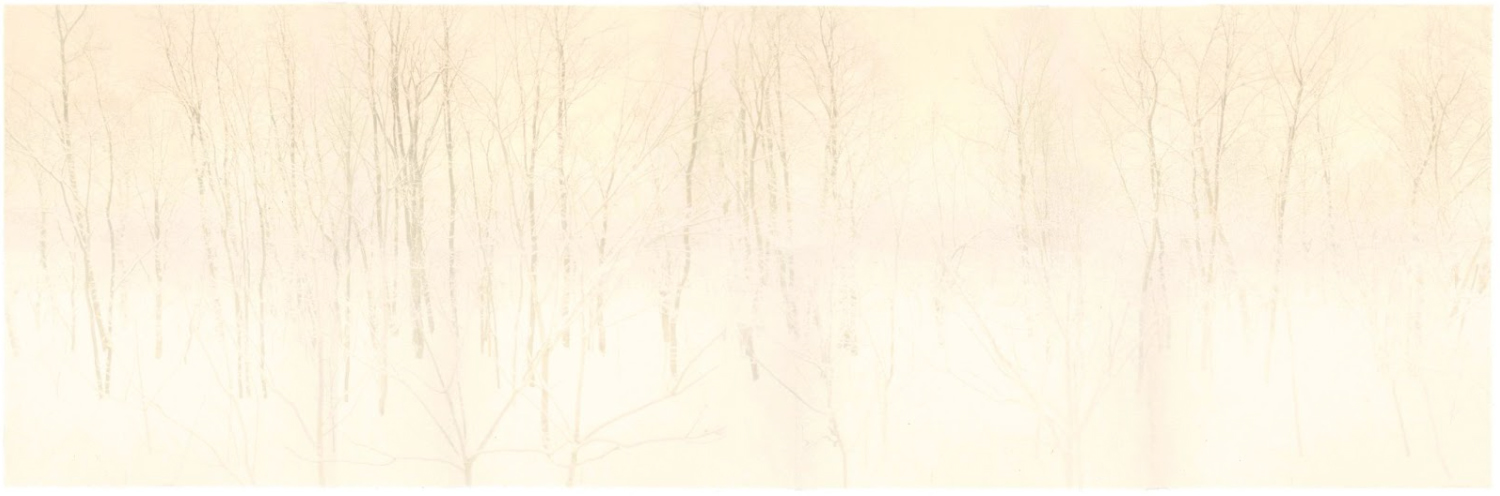

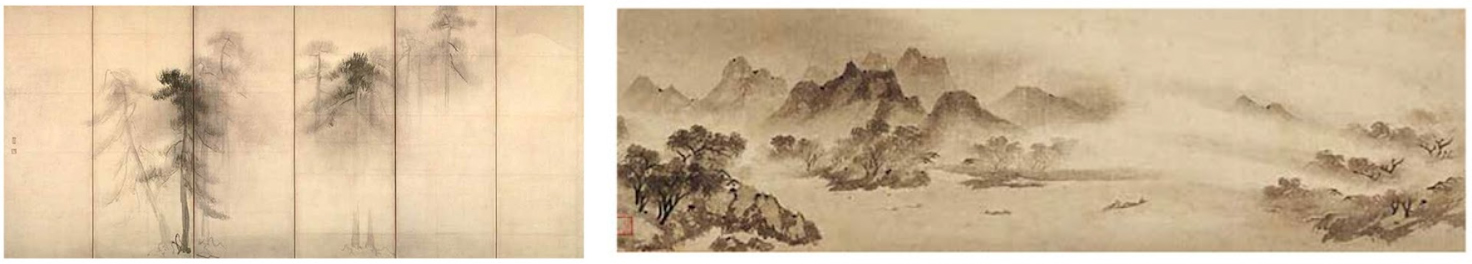

Okabe: Another work of yours which I think is related to ‘natural emptiness’ (自然余白) is “Winter Pine Trees in Genkai Landscape (寒松玄海図).” This work is well suited for the entrance of The Ritz-Carlton Fukuoka as it contains elements related to Okinoshima Island, Munakata Taisha, and the history of exchange between Kyushu and East Asia. I understand that you are interested in the ideas in Tohaku Hasegawa’s ink painting “Pine Trees (Shōrin-zu byōbu 松林図屛風)” from the Azuchi-Momoyama period. How did you approach the creation of this piece?

Lao: The Ritz-Carlton, Fukuoka is widely known as Kyushu’s premier hotel. The architecture itself, Fukuoka Daimyo Garden City, is also a representative facility of the modern redevelopment in Fukuoka. In this sense, the artwork at the entrance of this large. It was expected to be a gateway to a world of ancient legends of Kyushu and its interactions with East Asia.

This is why the work is related to the concept of ‘eternity’ (永遠) as well. Eternity, I believe, is not a finite time-based idea that humans objectify. As a comparison, eternity is like the realm of ideas in philosophy or the state of enlightenment in Buddhism. It is a state that transcends the limits of normal human life.

This idea is one of the reasons that Japanese tea rooms from the Muromachi period (1336-1573), which embodied ideas of Zen Buddhism in Japan, valued the work of Muxi (Mokkei 牧谿) (1210?-1269?) as his artwork represented the profound infinite atmosphere of ‘eternity’ (永遠).

In Eastern thought, “emptiness” is a central concept. Lao Tzu said, “Everything arises from nothing.” I believe that Hasegawa Tohaku, who was aware of Muxi’s works, realized “emptiness” at the lowest point in his life and from that created “Pine Trees (Shōrin-zu byōbu).”

Pine trees are also a symbol of a person of character. On the material side, “Winter Pine Trees in Genkai Landscape” is an installation work composed of countless dyed threads hung from the ceiling. Each dyed thread occupies a “moment” (間) and sways in the wind. This work shares the same spirituality with Tohaku’s “Pine Trees”. It is possible to deviate from the world of representation and catch a glimpse of “infinity and eternity” through the interdependence of emptiness and reality (虚実相生).

Ink on string 980×270 cm Daimyo garden city | The Ritz-Carlton Fukuoka collection – Entrance

福岡大名ガーデンシティ1階(ザ・リッツ・カールトン入口)に設置した作品

2-17階は商業施設、18-24階はザ・リッツ・カールトン福岡

Okabe: You mentioned earlier that it is the East that develops ideas based on “emptiness,” In asking you to talk about your work, I feel that it this philosophy is consistent with your spirit.

Lao: When I was traveling around for the coverage of pine trees for “Winter Pine Trees in Genkai Landscape,” I came across a statue on the Boso Peninsula in Japan that reflected the syncretism of Shintoism and Buddhism. It was beautiful, however the face was worn away from the passage of a thousand years. In Buddhist terminology, being free from all attachments is also called “signlessness” (無相) The work created from the statue using three-dimensional imaging technology has been acquired by the Asian Art Museum in Nice as part of its permanent collection.

artwork collected by Asian Art Museum in Nice, France (Permanent exhibition) ニース国立東洋美術館コレクション (常設)

Okabe: Lao, Thank you for showing us various works. You create your works by confronting various kinds of ‘dependant co-arising’ (縁起). You also consider the exhibition space (場) to be a kind of ‘dependant co-arising’ (縁起). You deepen your understanding of the installation location; sensitizing yourself to it. Then you install your works in a way that is appropriate to the place. In the Asian Arts Museum in Nice, designed by Kenzo Tange, I saw an installation of yours which looked like a three-dimensional mandala.

Lao: At the exhibition at the Asian Arts Museum in Nice, I had a great opportunity to experience the ideas of modernist architect Kenzo Tange with the additional support of Tange Associates and Yoyogi National Stadium in Tokyo The architecture is an example of Tange’s later work, built around the same time as the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building. This prestigious art museum incorporates elements of Eastern philosophy and garden architecture, and is fused with the earth.

In Esoteric Buddhism, the Mandala of the Two Realms is considered to encompass all life in the universe. When viewed from above, the exterior of the museum looks like a triangle, circle, and a square in that order. From this, we thought it was consistent with the Taizokai Mandala (Womb World Mandala), which is an image of compassion spreading into the world. The triangle in the center is the seated image of Dainichi Nyorai (Sanskrit: Mahāvairocana). The circle surrounding the center are eight Tathagata Nyorai Buddhas. The square are bodhisattvas surrounding the circle in all directions.

The Museum has a spiral staircase that runs through the center of the structure and serves as the axis for the museum. This staircase connects the basement located under the lake to the ground and upper floors. It can be interpreted as the Diamond Realm Mandala, which represents the path to enlightenment. I placed the 22-meter-long “Winter Pine Trees in Crescent-Shaped Landscape” (寒松三日月図) in there which is related to the Pure Land together with the ancient Buddha statues from the museum collection.

The ‘dependant co-arising’ (縁起) of the organic and non-organic is a poetic moment in which the macrocosm shines through due to the microcosm.

Okabe: Your works seems to invite viewers to enter a sublime worldview. The ideas expressed in you works, such as ‘natural emptiness’ (自然余白), ‘dependant co-arising’ (縁起) and the law of included middle (容中律) will certainly be of interest outside of art in fields such as phenomenology and philosophy.

Also, as you discussed with a researcher of Nishida’s philosophy, in modern times, we have progressed by exploiting nature based on the concept that nature is extremely vast; making our lives convenient. However, in the 20th century, a situation has arisen in which this view can no longer be maintained. It has been said that Nishida’s philosophy attracted attention during the Meiji era as a philosophy that could save us from exactly such a scenario.

Lao: I think the importance of Nishida’s research is that conscious phenomena are undivided into subject and object. Nishida says that everything in the world is an extrapolation out of this undivided awareness. I believe that this ‘undivided nature of subject and object’ (主客未分) and the law of included middle (容中律) can provide an opportunity to rethink the relationship between human beings and nature in the modern age.

Both Western and Eastern philosophies, while supporting human activities, suggest our true existence is in the phenomenal world. Art is capable of offering a glimpse into this dimension; a moment for true life to shine through.

France, English, Chinese, Japanese | ISBN : 9784865283815

Musée départemental des arts asiatiques

Adrien Bossard, Noritaka Tange, Hsin-Tien Liao, Koju Takahashi

Musée Guimet | Musée Cernuschi | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | 国立新美術館 | Princeton University

Okabe Rui is a curator at the Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art. She received her M.A. from Osaka University in 2009. Her major exhibitions include “"In Search of Light," a commemorative exhibition in honor of the donation by Tomonori Toyofuku” (2021, Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art) and “Donation Commemoration Exhibition: Nomiyama Gyoji” (2022, Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art).

Season Lao is a contemporary artist based in Kyoto, Japan. Born in Macau, He graduated from Macau Polytechnic University in 2010. In 2009, his video works about communities in Macau gained acclaim. This led to the preservation of historic buildings, including his birthplace, previously scheduled for demolition as people re-evaluated their importance. This inspired Lao to pursue his artistic work further. From 2010 to 2020, Lao was based in Hokkaido, Japan. His work during this time focused on the concept of “Engi (縁起)”or Dependent Co-arising. His artwork sought to capture the “interdependence of emptiness and reality (虚実相生)” in natural phenomena such as snow and fog. These works have since been exhibited around the world. Lao has been based in Kyoto since 2020. During the pandemic, he created site-specific works exploring the law of included middle (容中律) in places such as Pure Land Buddhist temple gardens. His installation works seek to dissolve the boundary between subject and object, re-exploring the relationship between human nature and the external world.

Public Collections Include: Macau Museum of Art, Museum of Asian Arts in Nice, Cernuschi Museum (Paris), Chishima Foundation (Japan), The Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Setsu Niseko, etc.